Note: Please see my video discussion of this topic below or other videos on my videos page. You may also want to read my PDF guide entitled Sensible Strategies to Reduce Your Taxes or other articles regarding retirement accounts on my Research page

This article discusses asset location and should not be confused with asset allocation. The latter refers to how your portfolio is allocated across different asset classes (e.g., 60% stocks/40% bonds). Once you have determined your asset allocation, asset location determines how those assets are distributed across types of accounts and investment vehicles with different tax characteristics.

As you may recall from my previous blog article, investment-related taxes are those which stem from your investment holdings. These include dividends, interest, rental income, and capital gains (e.g., via portfolio rebalancing or liquidation). These are different than the income taxes you pay on money you earn – which we discussed in my first blog article. However, it is worth noting that bond interest and rent (minus costs and depreciation) are also taxed as ordinary income. Please see the Income Stacking section of my previous blog article to understand how these interact with each other.

Given that asset location relates to both income and investment-related taxes, this topic could have been included in either of my previous two blog articles. However, I figured those articles were already long and complicated enough. Moreover, I find asset location represents lower-hanging fruit. That is, the relevant logic is fairly intuitive and you can often apply it almost instantly once you learn about it. For these reasons, I decided to carve it out and address asset location on its own.

Some preliminaries

Before we discuss the logic and strategy around asset location, it is helpful to understand how taxation differs across some of the primary types of investment accounts and investment vehicles. Please click to expand the boxes below for more details regarding how these accounts and vehicles are taxed.

- Taxable accounts: Standard brokerage (and living trust) accounts hold are 100% taxable when it comes to investment-related taxes. The same goes for interest-bearing bank accounts including certificates of deposit (CDs).

- Tax-deferred retirement accounts (TDA): These are your standard retirement accounts where you contribute money while you are working (401K, 403B, IRA, etc.). These contributions are (effectively) not taxed when you earn them. Moreover, this money can compound and grow without investment-related taxes. Ultimately, these funds will ultimately be taxed as ordinary income once they are distributed.

- Tax-free (i.e., Roth) retirement accounts: These are your Roth retirement accounts (e.g., Roth 401K or Roth IRA). Money in Roth accounts can also compound and grow without investment-related taxes. However, unlike TDAs, income taxes have already been paid on these funds and they can grow tax-free until the funds are distributed.

- Municipal bonds: Interest from municipal bonds is generally exempt from federal income tax. However, it may still trigger other taxes. For example, state and local taxes may still apply and municipal bond income is still included in other tax calculations (e.g., those that depend on MAGI). It is also worth noting municipal bond yields are typically lower than comparable taxable bonds with similar risk. So yields should be compared on an after-tax basis. Lastly, bond decisions should also account for portfolio effects since some types of bonds provide better diversification benefits than others.

- Annuities: These are products issued by insurance companies whose performance may or may not depend on one’s longevity. Annuities typically provide tax benefits that are similar to tax-deferred accounts (like IRAs). That is, there are not taxes on the growth within annuity products. However, the growth is eventually taxes as ordinary income (not capital gains) once it is distributed. While some are complex and have garnered criticism, not all annuities are bad; some allow for flexibility in financial/tax planning (lifelong income, tax exclusion ratios, etc.). For more on this topic, please see my articles on annuities here and here.

- Life insurance: Life insurance (if properly structured) is a unique asset in the sense there is no tax on its growth and the death benefit is tax-free as well (i.e., income or capital gains taxes do not apply) – similar to a Roth retirement account. While I think life insurance is oversold due to the incentives from its commissions, I do believe it can still be helpful in specific situations.

- Trusts: Trusts are separate legal entities created for the benefit of specific persons (beneficiaries) and managed by another party (a trustee – who may also be a beneficiary) on behalf of the beneficiaries. There are various tax implications for the creation and funding of trusts, the investment-related taxes within trusts, and the distributions made from trusts. While beyond the scope of this article on asset location, many trusts (e.g., irrevocable and charitable trusts) can be used for the purpose of tax efficiency (e.g., reducing investment-related, income, and estate taxes).

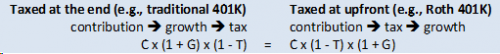

Some people claim it is better to pay taxes on money before it grows instead of paying a bigger tax bill (in absolute terms) after it grows. However, this logic is faulty. All else equal (tax rates, time horizon, and growth), paying tax at the outset or at the end results in the same exact amount of after-tax dollars being available at the end. The simple fact is that the tax rate applies multiplicatively and it does not matter what order you multiply numbers. If C is the original amount of the contribution, G is the investment growth, and T is the tax rate, then the amount of after-tax money at the end is the same:

Let’s follow what happens to $1 of retirement money when we contribute to a 401K that grows 10-fold to $10 while invested. The $1 becomes $10 via investment growth and then tax consumes $2.50 when it is ultimately distributed – leaving $7.50 to spend. Now let’s follow what would happen if we used a Roth 401K instead where we paid the tax upfront. In this case, we start with $0.75 in the Roth 401K and it grows 10-fold to $7.50 with no more taxes due. So the results are the same.

Truth be told, I brushed some details under the rug here; all else is not equal. For example, Roth accounts effectively allow for higher contributions. That is, we could have contributed one full dollar to the Roth if we had external cash on hand to pay the tax. Roth accounts also avoid required minimum distributions down the road. So that money may be able to enjoy the tax-shielding benefits longer than if they were forced out into taxable accounts.

On the flip side, taxes are typically lower during retirement. So it might make it more sensible to use traditional (non-Roth) retirement accounts. For more on these nuances, I went into significantly more detail here and here (warning: these articles are a bit more technical).

Asset location strategy

Now that we have listed the tax characteristics for various types of accounts and investment vehicles, we can start to think about strategies for where to place the assets you have decided to own (recall: the asset allocation decision takes priority). Unfortunately, there are too different factors that can determine your optimal asset location strategy.

- Relative levels of taxation on retirement accounts versus capital gains

- Likelihood of needing to liquidate assets during life

- Availability of step-up basis (politicians are discussing this notion)

- Longevity expectations

- Gifting intentions

- Tax credits + eligibility for various subsidies (e.g., affordable care)

- IRMMA (investment-related monthly Medicare adjustments)

- NIIT (net investment income tax)

- Taxation of Social Security (watch out for the torpedo!)

Given the number of factors involved as well as how they interact, financial planning software is required to truly optimize your asset location. Notwithstanding, here I highlight two primary rules of thumb that are both important and intuitive. In particular, you may be able to use these factors to quickly and easily make sensible adjustments to your own asset location.

The first rule of thumb

The first rule of thumb focuses on the tax efficiency/inefficiency of different assets. When it comes to investment-related taxes (i.e., from dividends, interest, and capital gains via portfolio rebalancing/liquidation), some asset classes or strategies are more tax efficient than others. Here are three examples:

- Funds or strategies with high turnover (e.g., hedge funds) would likely spin off significant short-term capital gains. Accordingly, these types of funds would typically be placed in a retirement account where those taxes would not apply.

- Taxable bonds and bond funds (i.e., not municipal bonds/funds) pay interest that is taxed as ordinary income. This makes them tax-inefficient as the tax on the interest can significantly reduce the benefits of compounding. Moreover, this is especially true for high-yield bonds where the yields (hence taxes) are higher. As a result, it often makes sense to hold taxable bonds and bond funds in retirement accounts as well.

Low-turnover stock portfolios and funds - especially exchange-traded funds (ETFs) - are typically much more tax efficient. Less turnover leads to fewer capital gains but the dividends they pay (assuming they are qualified) are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate – not as ordinary income. So it often makes sense to hold these in taxable accounts.

The second rule of thumb

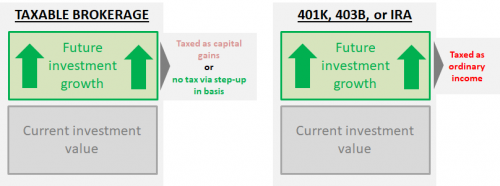

The second rule of thumb I highlight relates to growth expectations. Recall that tax-deferred retirement accounts (e.g., 401Ks, 403Bs, and IRAs) will ultimately be taxed as ordinary income. Thus, if you grow your traditional IRA, then you will also grow your tax bill too. So that may be the last place you want to place higher-growth assets. Instead, it is generally better to hold them in either Roth or taxable accounts.

In a Roth account, the growth will be tax-free. So this can be the ideal location for higher-growth assets like stocks over the long term. Of course, if you experience gains in a taxable brokerage account, then those gains will be taxable. However, this growth is only taxed as a capital gain (not ordinary income). Moreover, if you were to hold this asset throughout retirement and pass it on to heirs, then it would receive a step-up in basis. In particular, this would result in no tax on the growth (assuming current tax law and the taxes on dividends along the way).

Tax on investment growth

Parting words

I find asset location offers low-hanging fruit in terms of an opportunity for investors to reduce their taxes. The factors I described above should help in understanding some of the logic involved. However, as with other areas of financial planning (especially those involving taxes), I strongly advise utilizing a financial planner who uses financial planning software that is devoted to this purpose. I prefer Income Solver due to its superior calculation engine even if its interface and reports are less glamorous than other packages.

Unfortunately, I find many advisors opt for planning software packages that are easier to use and create more aesthetic (interactive) reports to show to their clients. Moreover, I believe it is also important for financial planners to augment software output to address areas the software does not (e.g., disclaiming and beneficiary strategies – see my video discussion of this topic on my videos page).

Related content

- Illustrating the Value of Retirement Accounts

- Quantifying the Value of Retirement Accounts

- Video discussion of this topic on my videos page

- My PDF guide entitled Sensible Strategies to Reduce Your Taxes

You may also learn more about me and my firm here: